College Admissions Trends

College Admissions Trends

Here’s what’s going on with the Common App right now and why juniors need to pay attention heading into next fall:

Key Trends from the Common App

More Students Are Applying

Applications are up across the board. The pool is bigger, which means competition is too.

Early Action Is Exploding

Early Action applications jumped 17%. More kids are trying to get in early, and colleges are responding by getting pickier.

First Generation Applications Are Rising

Applications from first generation students are up 15%, which is an important shift in the applicant landscape.

Diversity Continues to Grow

Latinx and Black or African American students are among the fastest growing applicant groups, with 14% of students identifying as one of these backgrounds.

Half of Students Are Still Submitting Test Scores

Even with test optional policies, 50% of applicants are choosing to report SAT or ACT scores.

Public Universities Are Getting Flooded

Applications to public colleges are up 11%, which is more than double the growth rate of private schools.

What This Means for Juniors

If you are a junior, these trends matter. A lot. Here are the biggest takeaways I want families to understand right now:

Test Scores Are Not “Dead”

Everyone loves to say testing does not matter anymore. That is not actually what is happening. Even though most schools are technically test optional, more students are submitting scores every year, and that trend is growing fast. Translation: scores still help. If you can submit a strong score, it can absolutely give you an edge.

If you are applying without scores, that is okay, but you need to be smart about your list. Not every school evaluates test optional applicants the same way, and you should do your research early.

Public Schools Are Getting More Competitive, Especially in the South

Big state schools are having a moment. Southern publics in particular are seeing huge surges in applications. They are amazing schools, but out of state admissions can be brutal because they prioritize in state students. This is why I always tell juniors: do not build a list with only public flagships. Private colleges often admit more out of state students and can offer serious merit money, which can make them just as affordable.

Early Action Is No Longer the “Easy Round”

Early Action is growing fast, and that means it is getting more competitive. Colleges are also deferring more students instead of giving early yeses. So strategy matters. If you have a true top choice and you are financially able to commit, Early Decision can be a powerful option. And every junior should have at least one rolling admissions school on their list so you are not waiting until March for your first decision.

Final Thoughts

The college process is changing every single year, and juniors who start planning now are going to be in the best position next fall.

Bigger applicant pools, more early competition, more testing being submitted, and public universities getting slammed with applications means one thing:

You need a smart, balanced strategy, not just a dream list.

Your GPA and SAT Don’t Define You-But Context Does

Your GPA and SAT Don’t Define You-But Context Does

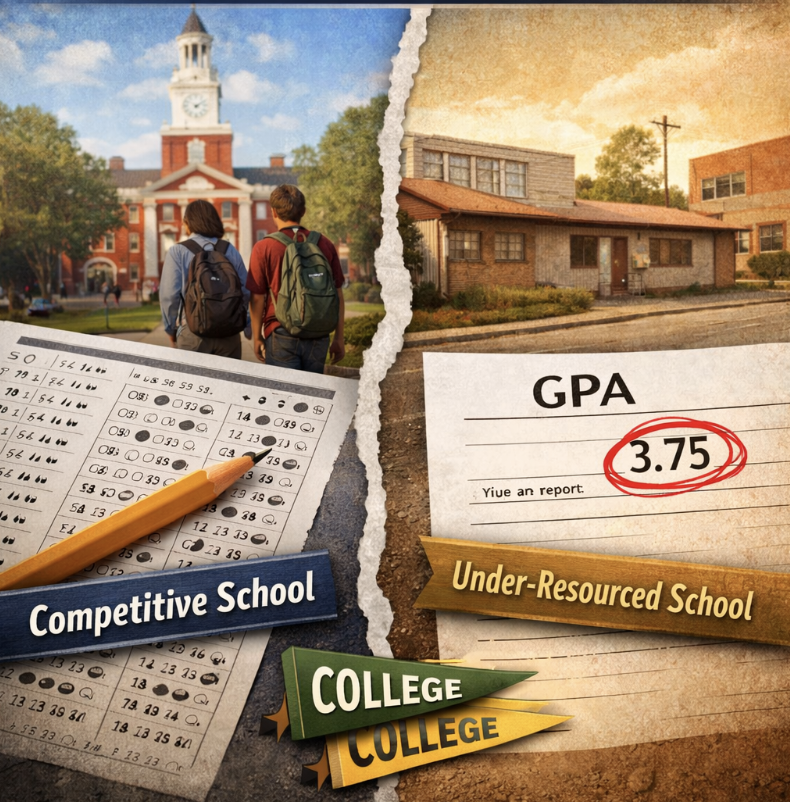

A 3.75 GPA and a 1400 SAT can be amazing at one high school… and completely average at another.

That’s the part students don’t fully understand until decisions start coming out:

Stats don’t speak for themselves. Context speaks for them.

I met with a student recently who had been denied from several of their top-choice schools. They were confused, because on paper, they looked like a strong applicant.

They kept saying: “But I’m right in the school’s range. I thought it was a target.”

And honestly? That mindset deserves its own post.

Most students misunderstand what a “target” school is.

A school is not a target just because your GPA and SAT fall in the middle 50%.

When a college gets 50,000+ applications filled with academically qualified students, admissions officers aren’t sorting by numbers.

They’re shaping a class.

From the college’s perspective, it’s a dream: endless qualified options.

For students, it can feel unpredictable and personal, even when it isn’t.

Let’s talk about the famous “3.75 and 1400.”

Those are strong numbers. Period.

A student who earns them has worked hard and should be proud.

At many colleges, that profile would be more than enough.

But selective admissions always comes with an asterisk:

Strong doesn’t always mean standout.

Now here’s where context matters.

Scenario 1: The hyper-competitive prep school

At a school where nearly everyone goes to a four-year college and many land at top universities:

A 3.75 GPA might put you in the middle of the class

A 1400 SAT might be completely expected

You don’t look exceptional… you look typical

Not because you aren’t impressive.

Because everyone around you is also impressive.

Scenario 2: A school with fewer resources and fewer college-bound students

Now take that exact same student and place them in a high school where only 30% of graduates attend a four-year college.

Suddenly:

That GPA could be top 10%

That SAT score might be one of the highest in the class

The student has maximized every opportunity available

Same stats.

Totally different story.

And admissions officers know that.

This is why “I got rejected with a 3.75 and 1400” means nothing by itself.

Because the real question is:

Rejected compared to who? In what environment? With what opportunities?

Colleges don’t evaluate numbers in isolation.

They evaluate students relative to their school, community, and access.

Lee Coffin, Dartmouth’s Dean of Admissions, recently said it clearly:

They evaluate testing “in the context of the school environment.”

He also shared that nearly 92% of admitted students have scores in the top 25% at their high school.

Not nationally.

At their school.

That’s the key.

So what should students actually do?

Before building your college list, look deeper than the headline stats.

Ask:

How competitive is the applicant pool?

How many students apply vs. how many are admitted?

What percentage of enrolled students were top 10% or top 25% of their class?

How does your transcript compare to your school profile?

You can often find this in the Common Data Set, though some colleges are more transparent than others.

The goal isn’t obsession.

The goal is realism.

GPA and SAT are one piece of the puzzle.

They can help open the door.

They do not guarantee you walk through it.

What matters just as much (and sometimes more):

Course rigor

How you challenged yourself within your environment

Leadership and activities

Essays

Impact

Fit with the college’s goals that year

And that’s before you even factor in institutional priorities, yield, financial aid, and everything else behind the scenes.

Admissions is complicated.

A 3.75 and 1400 might be a golden ticket at one school…

And totally unremarkable at another.

So instead of treating college as a prize to win, think of it as a match to make.

The right school is where you will thrive — academically, socially, personally.

And if a decision doesn’t go your way?

It’s not a rejection of your worth.

It’s a redirection toward the place that fits.

You will end up where you’re meant to be.

What to Do If You’re Deferred

What to do if deferred

If you have been deferred, take a breath. Truly. A deferral is not a rejection—and in many cases, it’s an opportunity.

Most colleges actually view Early applicants favorably in Regular Decision. These students raised their hands early and demonstrated genuine interest from the start. Admissions is essentially saying: We’re not done with you yet.

The key now is to be strategic.

Strengthen the Story

Grade trends

Positive momentum matters. A strong first-semester senior transcript can legitimize an upward curve and give admissions officers a reason to take another look.Clarity of personal narrative

Does the application clearly show who this student is, what motivates them, and the role they’re likely to play on campus and beyond?Depth and commitment in extracurriculars

Colleges care less about how many activities a student does and more about impact, leadership, and sustained engagement.

Build Momentum

Once other applications are submitted, shift focus back to the deferred school.

This is the time to:

Lean into meaningful winter or spring activities that align with the student’s core interests. These don’t need to be flashy—they need to be real and substantive. This work will later fuel a strong update letter.

Identify an additional recommender, if appropriate. A coach, mentor, research advisor, or supervisor from a key extracurricular can be especially effective—someone who can speak to recent growth, leadership, or community impact.

Craft the Update Letter

A well-written update letter can make a real difference. It should be formal, thoughtful, and sent both by email and mail.

A strong update letter should:

Address the regional admissions officer by name

(Your school counselor can help, or this can usually be found online.)Provide concrete updates

New grades, leadership roles, projects, test scores, or initiatives. This is the moment to directly address any earlier weaknesses and show progress.Reaffirm interest clearly and honestly

If the school is a top choice and you would attend if admitted, say so. If you’re unsure, you can express strong interest—but know that clarity carries more weight.Reconnect your goals to the school

Reference specific programs, opportunities, or experiences you haven’t already discussed, and explain how they fit your academic and personal direction.Offer to connect directly

A simple line offering to speak by phone or Zoom shows maturity and genuine engagement.

Strategic Reminders

Prioritize quality over quantity in updates.

Make sure each new development adds something new to the application.

Keep performing strongly in current commitments—senior grades still matter, often more than students realize.

Most importantly, remember this:

A deferral means the college sees potential. They just want more information.

I’ve seen many students approach deferrals thoughtfully and intentionally—and go on to be admitted to schools they once thought were out of reach. This is not the end of the story. It’s just the middle.

A Practical Guide to the Common App College Essay (What actually matters—and why)

Common App Essay

When I talk to students about the Common App essay, I usually boil it down to three things. A strong college essay should be:

I. Memorable

II. Relevant

III. Personal

That’s it. Three words. But of course, the pushback always comes fast:

What about “well-written”?

Fair question. If part of my job is helping polish essays, shouldn’t “polished” matter? And if this essay is meant to showcase a student’s best thinking, shouldn’t it be—at least on some level—impressive writing?

Yes. And also… not in the way most people think.

What “Well-Written” Actually Means

Here’s the reframe I want students (and parents) to understand:

In college admissions, “well-written” does not mean literary.

Your essay is not being read by a panel of novelists. It’s being read by admissions officers with wildly different academic backgrounds—science, policy, history, economics—who are moving quickly through stacks of applications.

The strictly literary stuff—beautiful turns of phrase, elegant structure, clean flow—almost always emerges naturally during revision. That’s not the differentiator.

What is the differentiator is this: Unique writing signals a unique student.

Grades, scores, and resumes blur together. Personality does not.

A 3.9 GPA with leadership roles and awards is impressive—but at selective colleges, it’s also common. Once a student clears the academic bar, admissions officers stop asking “Can this student do the work?” and start asking:

Why this student? What do they bring that others don’t?

Sometimes the answer is a once-in-a-generation athletic or academic achievement. Most of the time, it’s the essay.

The essay is where a student shows humor, empathy, self-awareness, creativity, and the ability to reflect—not just grind. It’s the difference between being the fastest hamster on the wheel and being the student who steps back, questions the wheel, and builds a better one.

That’s why I always come back to three questions.

Question One: Is It Memorable?

Memorable essays don’t rely on shock value or dramatic life events. They rely on specificity and storytelling.

A memorable essay:

Pulls the reader into concrete scenes—people, moments, sensory detail

Is structured intentionally (often starting in the middle of something, not at the beginning of time)

Leaves the reader with images they can recall later

Here’s the reality admissions officers won’t say out loud:

They are tired. They are hungry. They’ve read dozens of essays already.

So ask yourself:

If it’s five minutes before lunch and your reader hasn’t slept enough, what keeps them from skimming?

If it’s later that night and they’re replaying the day’s essays in their head, why is yours the one that sticks?

The answer, almost always, is small but meaningful moments, not big résumé events. Essays about subtle realizations, quiet failures, or shifts in perspective tend to linger far longer than essays about championships, awards, or tragedies treated at a distance.

If your essay isn’t memorable, your reader won’t fight for you—because they might not remember you at all.

Question Two: Is It Relevant?

Your essay should feel deeply personal and clearly connected to the rest of the application—without repeating it.

Think of the essay as the lens through which the admissions officer interprets everything else.

There are two broad types of students colleges see all the time:

1. The Jack-of-All-Trades

These students do everything: a little tutoring, a little volunteering, a little sports, a little STEM. The risk here isn’t lack of effort—it’s lack of coherence.

Admissions officers may wonder:

What will this student actually do on campus?

What matters most to them?

Is there a core identity—or just a packed calendar?

The essay’s job is to quietly reveal the through-line—without listing activities or turning into a cover letter.

For example, a student who tutors, skis, builds robots, and volunteers might uncover a deeper pattern: one-on-one problem-solving, physical awareness, helping others improve performance. The essay can tell a story that embodies those values, while supplements handle the logistics.

Sometimes this also means minimizing or letting go of activities that don’t support that core narrative—and that’s okay.

2. The Specialist

These students have a clearer path—athletes, artists, activists. Their activities already show commitment and direction.

For them, the essay shouldn’t re-explain the résumé. It should answer a different question:

Why does this matter to you?

The most common trap here is the origin story: “Here’s how I started skiing / painting / singing / debating.”

Background isn’t enough. Colleges want to see how you’ve set your own standards, questioned assumptions, and grown within that passion.

In both cases, activities should be the context, not the point. The essay should always be about character.

Question Three: Is It Personal?

“Make it personal” might be the most overused—and least helpful—piece of advice in college counseling.

Students hear it and freeze. What does that even mean?

Here’s what it does not mean:

Writing a polished summary of achievements

Ending with a generic moral

Turning struggle into a highlight reel

A truly personal essay does something harder: It shows self-interrogation.

Admissions officers are quietly asking:

Can this student reflect honestly on failure or limitation?

Can they recognize flaws in their thinking and adjust?

When things don’t work, do they just try harder—or think differently?

What role will this student play on campus that no one else can play quite the same way?

And the unspoken final question:

Is this real—or is this BS?

The essay is the best bullshit detector colleges have.

Students who only present success often haven’t pushed themselves to the point where something didn’t work. The strongest essays come from moments where students had to redefine success altogether—learning to live with constraints rather than “overcome” them.

The student who can’t fix a family situation but finds independence anyway.

The student who won’t “beat” a disability but builds a different relationship with learning.

The student who stops chasing perfection and starts building meaning.

These stories resonate because they’re honest—and because they show adaptability, humility, and growth.

The Bottom Line

Admissions officers are human. They want their campus to be full of people who will:

Lead clubs

Debate ideas

Create art

Challenge each other

And be people others actually want to be around

Colleges invest in students not just for past performance, but for future contribution.

A truly personal college essay makes the reader care. It makes them pause. It makes them want to reread—and maybe even talk about it later.

That’s the bar.

And if an essay gets someone to say, “I need you to read this one,” then yes—that’s when a college essay has done its job.

Weighted vs. Unweighted GPA: What's the Difference?

Do colleges look at weighted or unweighted GPA? Is weighted or unweighted GPA more important? What is cumulative GPA?

Whether your child is applying to college soon or you’re just planning ahead, you likely know that grade point average (GPA) is one of the factors colleges consider when making admissions decisions. You might, however, have questions like “What’s the difference between weighted and unweighted GPA?” or “Which GPA do colleges care about?”

Maintaining a high GPA is probably one of the most challenging responsibilities of your college-bound high school student. It requires consistency and deliberate study, but also a little bit of strategy.

You may have heard, for instance, that colleges want both great grades from applicants and a rigorous course load. But what if your child can earn straight As taking regular classes, rather than earn Bs on the AP or IB track? Should they play it safe and go for the easy A?

Let’s take a step back. Sure, a strong GPA is a key part of any college application, and it’s certainly one of the first elements that any admissions officer will check when reviewing your child’s file. But there are several other factors that admissions officers are considering when presented with this number.

You may have heard about “holistic admissions,” a process by which applicants are evaluated for qualities outside of grades and SAT or ACT scores. This means that colleges are looking to see if your child has made the most of the opportunities available to them. Colleges want to see that your child has challenged themselves academically by selecting courses that align with their strengths, interests, and career goals. A student whose high school has twenty AP classes available is not treated the same way as a student whose high school has zero or one.

In other words, a 4.0 vs. a 3.8 vs. a 3.5 means nothing without knowing your child’s course history, your child’s high school’s course offerings, the academic opportunities available to your child, etc.

So, yes, the number matters—but so does the context in which that number was achieved.

What’s the difference between weighted and unweighted GPA?

Your child’s GPA is the average of how well they perform in their classes. But it’s not necessarily a simple mean (i.e., mathematical average). The GPA can also represent how difficult those classes were—in other words, how much your child challenged themselves by going as far as possible in a given field. If you’re the parent of a younger high school student and you take nothing else away from this article, take this: encourage your child to select challenging courses in their areas of interest. For example, if your child loves science and aspires to become a doctor, AP Biology would be a good option if their school offers it.

But wait. Won’t encouraging your child to challenge themselves come at the risk of a lower GPA? What if your child likes AP biology but might earn a B on the harder track? Why not let them make an A in regular biology, even if that means they ultimately won’t be challenged as much?

Luckily, high schools across the nation have come up with a way to address this dilemma. Your child will probably have two numbers that matter on their college application:

Their unweighted GPA, the simple mean of all their grades over four years

Their weighted GPA, which takes into consideration the difficulty of each course

In a standard, unweighted GPA, an A receives a 4.0, a B receives a 3.0, and so on. In the unweighted system, coursework difficulty is not accounted for. This means that an A in AP Biology counts the same as an A in regular biology, and both of those count the same as an A in a physical education course.

By this system, in theory, a student who took all the easiest coursework and breezed through their classes could end up with a 4.0, possibly surpassing the students who took on the heavy lifting of enrolling in five AP classes in a single semester. In a typical weighted GPA, AP or other advanced classes correspond to a higher number, so when they’re averaged in with the less difficult classes, they contribute more strongly to the average, thereby pulling the overall GPA higher. For example, an A in an AP biology class could equate to a 5 in your child’s GPA, whereas an A in a regular biology class only counts for 4. Therefore, your child is rewarded for challenging themselves, both in the numerical GPA and also when (especially when) the admissions officer delves into your child’s course history.

Do colleges look at weighted or unweighted GPA?

Remember that colleges aren’t looking at GPAs out of context. After checking the GPA on your child’s high school transcript, the very next thing an admissions officer does is dig into the listed courses. Within seconds, they’ll be able to assess the rigor of your child’s coursework and immediately contextualize your child’s GPA compared to those other piles of transcripts stacked on their desks.

The student who took all the easy courses and earned a 4.0 won’t get into an Ivy League school. However, the student who earned a 3.7 taking the most challenging courses offered while balancing extracurricular commitments is a competitive candidate.

That said, not every college takes such a holistic approach to admissions. Large public universities, because they often receive a far greater number of applicants than small liberal arts colleges do, often sort applicants based on whether they meet a minimum GPA requirement.

For example, the University of North Carolina requires a minimum GPA of 2.5 (weighted) to be considered for admission. These minimums don’t guarantee admissions; on the contrary, they limit the admissions committees’ holistic assessments to only those applicants whose GPAs are above their minimum standard.

Further, most scholarships at these types of schools require a GPA above the general admissions minimum. So, whereas a 2.0, whether it’s a weighted or unweighted GPA depending on the school, might qualify your child to apply, they may need a minimum of a 3.0 to qualify for financial scholarships. But remember: these are minimums, so the rigor of your child’s course load is still considered when the admissions teams evaluate transcripts.

With all this pressure placed on GPA, it should comfort you to know that most high schools that offer varying degrees of course difficulty to their students also calibrate their GPAs accordingly. This calibration, the weighted GPA, typically works on a 5.0 (rather than 4.0) scale.

Though not every high school calculates their weighted GPAs the same way, they do communicate their methods to colleges. If your child’s school has nontraditional approaches to grades or doesn’t have a standard practice for weighting, you can talk to your child’s guidance counselor and request that they provide as much information as possible in the counselor recommendation that they write for your child.

If your child took courses at a community college and wants to see that weighted accordingly on their transcript, this again should be brought to the guidance counselor’s attention, as it will likely need to be addressed on a case-by-case basis (unless your child’s school already has a defined system in place, which they would communicate to colleges).

Here’s the bottom line: regardless of whether your child’s GPA is weighted or unweighted, colleges will consider that number in the context of the coursework they took and that was available to them. In addition, it will be clear to admissions officers whether the GPA is weighted or unweighted. So, if your child’s high school only provides an unweighted GPA, don’t worry that this will look bad when compared with the weighted GPAs of other applicants.

Calculating weighted and unweighted GPA

How to calculate unweighted GPA

Let’s get into the nitty gritty and show you how to calculate each type of GPA, beginning with unweighted. Here are hypothetical course histories for two students who we’ll call Mario and Danielle. Remember that, with an unweighted GPA, an equal number of credits is associated with each class.

Mario

AP Biology: A

AP English: B

AP US History: A

AP Calculus: A

Danielle

Earth Sciences: A

American Literature: B

World History: A

Algebra: A

Now, let’s crunch the numbers:

Mario gets a 4.0, 3.0, 4.0, and 4.0. Those numbers summed and divided by 4 (the number of courses) give Mario an unweighted GPA of 3.75.

In an unweighted system, an A is an A and a B is a B (regardless of course difficulty,) so Danielle would end up with the same GPA of 3.75.

Both appear equal in this system, but they’re not. The college admissions officer will take note of Mario’s rigorous course load and weight it accordingly when making her decision.

How to calculate weighted GPA

A typical weighted GPA works on a 5.0 scale, which allows for advanced courses (like those in AP and IB) to be scored a point higher than standard classes. So, using the same course list from above:

Mario, who only had AP courses, gets a 5.0, 4.0, 5.0, and 5.0. Those scores summed and divided by 4 (the number of courses) gives him a weighted GPA of 4.75.

Danielle, on the other hand, still gets a 4.0, 3.0, 4.0, and 4.0—and a 3.75 weighted GPA.

Mario wins, both numerically and in the eyes of the admissions officer.

However, let’s hypothesize that Mario did less well in his coursework than Danielle did because the courses he took were tougher. Let’s say Mario earned the following grades:

Mario

AP Biology: B

AP English: C

AP US History: B

AP Calculus: B

In a weighted GPA, Mario’s grades would result in a 3.75 GPA (4.0, 3.0, 4.0, and 4.0 summed and divided by 4), matching Danielle’s GPA despite having technically lower letter grades.

As you can see by this calculation, the weighted system plays in the favor of those students who challenged themselves with their coursework and rewards them with higher numerical contributions per letter to their overall GPA.

In some cases, schools might grade out of 100% rather than use a 4.0 or 5.0 scale. But no matter how your child’s grades are calculated, an admissions officer will consider course rigor.

Frequently asked questions

Which should your child report to colleges, a weighted or unweighted GPA?

Your child likely won’t get to choose which GPA colleges see. Your child’s high school has likely long established what kind of grading system they report to colleges. If you do get to choose, it’s almost always in your favor to choose the weighted GPA because it reflects both the earned scores and course difficulty.

What if your child’s high school doesn’t offer AP courses?

Let’s face it: not all high schools are created equally. Some high schools don’t offer AP or IB courses, and so their graduates—the best of whom boast a 4.0—will be forced to compete with other applicants with a 5.0.

Again, let’s take a step back and remind ourselves what it is that college admissions committees really care about: whether your child made the most of what was available to them.

If your child took the most challenging courses available, they’ve demonstrated drive and commitment to their education. A counselor or teacher letter of recommendation can help make that clear by placing your child’s accomplishments in the context of the school—for example, “Johnny is the first student to take every honors class our school has to offer.”

If your child is a freshman or sophomore planning for future coursework and you see that your high school doesn’t offer AP courses, look for offerings outside of the school setting. For example, can your child enroll in an online AP class or self-study for the AP exam? Can they take a class at the local community college?

Even if those alternatives won’t contribute to your child’s numerical GPA due to their high school’s unweighted system, admissions officers will appreciate that your child went above and beyond to further their education. It will go a long way in proving to the admissions committee that your child took the onus onto themselves to follow their passion beyond limitations. That’s the kind of grit and initiative an admissions officer wants to see.

How are UC GPAs calculated?

If your child is applying to University of California schools, you may have encountered yet another type of GPA: the UC GPA. The UC GPA is considered a “weighted, capped GPA” because the formula adds extra points for honors-level courses yet limits the courses taken into account. Only “A-G” courses (i.e., academic or art classes) taken between the summer after 9th grade and the summer after 11th grade may be considered.

This can result in your child’s UC GPA differing from their weighted and unweighted GPAs. For example, if your child’s grades were poor freshman year but improved subsequently, their UC GPA might be higher than either their weighted or unweighted GPA.

On the other hand, if your child has loaded up on AP classes, their UC GPA might wind up being lower than their weighted GPA. That’s because the UC GPA limits the number of extra points that can be awarded for honors-level courses.

You can read more about the UC GPA formula here.

What about colleges that recalculate GPAs?

Like UC schools, some colleges recalculate all applicants’ GPAs so they are on the same scale in order to make it easier to evaluate prospective students. Your child’s recalculated GPA might vary from school to school, since colleges with this practice may have differing formulas.

At Oberlin, admissions officers calculate an unweighted GPA based on core academic classes (i.e. no electives, vocational courses, or independent studies). University of Michigan does the same but uses the absolute value of grades (i.e., an A+, A, and A- are all a 4.0) earned between freshman and junior year. And some schools, like Stanford, recalculate GPAs without freshman year grades.

If a college recalculates GPAs, it’s likely that they also use the recalculated numbers when evaluating students for scholarships or when reporting their average incoming GPA. So, it’s worth researching the GPA policies of each school on your child’s college list.

Final thoughts

GPA matters but it’s only a piece of the admissions puzzle. Encourage your child to take challenging courses that align with their strengths and interests. Complement those passions outside the classroom with a unique extracurricular profile, stellar personal statement, and thoughtful supplemental essays, and your child’s application will speak for itself, far beyond the limitations of that nagging little number posted at the top of your child’s transcript.

The Best Summer Programs for High School Students

The Best Summer Programs for High School Students

For many parents of high-achieving students, summer break brings a familiar dilemma: how to balance rest and fun with meaningful productivity. As you plan ahead, you may be exploring summer programs that expand your child’s interests and strengthen their college applications.

In recent years, pre-college summer programs—especially those on college campuses—have exploded in number. Some offer rigorous, academic immersion, while others blend enrichment with a structured, enjoyable summer experience that can add depth to college essays.

With so many options, the real question becomes: which programs are truly worth the time, effort, and often high cost?

Your child could spend the summer in a wilderness program, volunteering abroad, attending an arts camp, or joining a specialized institute tied to an activity they love—such as robotics, debate, or an academic team.

For academically curious “bright generalists,” pre-college programs on college campuses have grown rapidly. These programs are designed to simulate college life, with courses taught by professors, students living in dorms (or commuting locally), and added lectures, networking, and social activities. They typically last one to eight weeks.

Pros

Deeper academic or hands-on study than most high schools offer

Early exposure to college life, easing the eventual transition

Insight into different campus environments and school types

Possible college credit or advanced placement

Potential relationships with instructors for recommendations

Opportunities to meet like-minded peers

Cons

Often very expensive (e.g., $6,500 for two weeks at some programs)

Quality, rigor, and selectivity vary widely and don’t always match the host school’s reputation

With a few elite exceptions, these programs rarely provide a direct admissions advantage—name recognition alone isn’t worth the cost

Although pre-college programs now exist at many elite colleges, their selectivity and rigor vary widely. In many cases, schools simply rent out their name and campus to for-profit companies during the summer, or house programs within divisions that are largely separate from undergraduate academics and admissions.

As a result, while the instruction may still be strong, acceptance rates are often high for students with solid grades and the ability to pay full tuition. That lower selectivity means that attending a summer program at an elite college does not carry the same weight or prestige as being admitted to the college itself.

Will a summer program help your child get into that college?

Short answer: probably not—at least not directly. Most pre-college programs have no influence on undergraduate admissions and should not be seen as a backdoor in. Admissions officers know many of these programs have high acceptance rates and high price tags, and—outside of a few elite programs—attendance alone isn’t considered a major achievement.

That said, pre-college programs can still be worthwhile if they genuinely align with your child’s interests. Strong instruction, exposure to college-level work, and the chance to deepen an academic focus can all strengthen an application indirectly. What matters most is not the name of the program, but how your child grows from it—and how that growth shows up in their essays, activities, and future pursuits.

For example, a student deeply interested in Russian might meaningfully benefit from an intensive language program, even if it doesn’t confer admissions prestige. The real value comes from increased skill, intellectual curiosity, and sustained commitment—not simply attendance.

The same principle applies to non-academic programs and volunteering. Service should reflect genuine interest and long-term commitment, not a flashy or expensive attempt to impress. Short-term volunteer trips abroad, in particular, can raise ethical concerns if they offer limited impact or primarily benefit the participant.

In most cases, meaningful service close to home allows students to make a deeper, longer-lasting impact. That said, volunteering abroad can make sense if it clearly connects to a student’s interests and offers opportunities unavailable locally—and if the organization is ethical, community-centered, and well-run.

Whether volunteering locally or overseas, the goal should be sustained involvement. Students should look for ways to stay engaged long-term—through fundraising, remote work, or ongoing collaboration—so their efforts reflect real commitment and meaningful impact rather than a brief experience.

There are more quality summer programs for high school students than we could list, but here are some of our favorites, organized by category. We focused on programs that are selective, often free, and academically or otherwise rigorous.

Most of our picks are U.S.-based and academically oriented, though a few fall outside these parameters. Ultimately, the best program for your child is one that aligns closely with their interests—whether that’s architecture, jazz guitar, or another niche passion.

General academic summer programs for high school students

Anson L. Clark Scholars Program

Description: The Clark Scholars Program is an in-depth research program that is open to students 17 years and older in the following disciplines:

Biology/Cellular & Microbiology

Cancer Biology

Chemistry

Computer Science

Electrical and Computer Engineering

History

Mechanical Engineering

Physics

The program features one-on-one research with faculty, as well as weekly seminars, discussion, and field trips. The Clark Scholars Program is very competitive, with only 12 students accepted each year.

Location: Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX

Cost: Free with on campus meals, room and board, and weekend activities provided.

Length: 7 weeks

Notre Dame Leadership Seminars

Description: Leadership Seminars is for current high school juniors who are academically gifted leaders in their school, church, local community, or other social organizations. Students participate in one of three seminars (sample topic: Global Issues: Violence and Peace in the Modern Age). Around 120 students are admitted each year—usually ranking in the top 10 percent of their class—and are eligible to receive one college credit.

Location: Notre Dame University, Notre Dame, IN

Cost: $150 enrollment fee

Length: 10 days

Telluride Association Summer Seminars (TASS)

Description: TASS offers college-level, academic seminars for current high school sophomores and juniors that allow them to “develop critical reading and writing skills and explore the principles and practice of democratic community living.” TASS currently offers two seminars: Critical Black Studies and Anti-Oppressive Studies, and the program prioritizes group discussion, writing, reading, and self-governance. TASS is a new program replacing the highly selective TASP, which admitted around 5 percent of applicants.

Location: Various college campuses across the United States (2025 locations are Cornell University and the University of Maryland)

Cost: Free

Length: 5 weeks

Math summer programs for high school students

(Note: Some programs in the following category also include math.)

Program in Mathematics for Young Scientists (PROMYS)

Description: PROMYS is a program for mathematically gifted students which focuses on “the creative side of mathematics.” Open to all high school students over 14 years old, students attend lectures, take advanced seminars, conduct research, and work on problem sets individually or in groups. Around 80 applicants are accepted each year, a quarter of whom are returning students.

Location: Boston University, Boston, MA

Cost: $7,000 (financial aid is available, and the program is free for families earning under $80,000 per year)

Length: 6 weeks

Description: Ross students focus deeply on one subject, number theory, for the entire duration of the program and spend most of their days working on challenging problem sets. Ross aims to provide its participants with an initial step towards their own mathematical research. Open to all high school students, Ross typically admits around 20 percent of applicants—around 70 students each year.

Location: (2 sites in 2025): Otterbein University in Columbus, OH

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology in Terre Haute, Indiana

Cost: $7000 (financial aid available)

Length: 6 weeks

Stanford University Mathematics Camp (SUMaC)

Description: SUMaC is a program for sophomores and juniors consisting of lectures, a guided research project, and group problem solving. Focused on pure mathematics, SUMaC students choose one of two course topics, both of which delve into mathematics topics from historical and contemporary research perspectives.

Location: Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA

Cost: $7,000 (financial aid available)

Length: 3 or 4 weeks

Description: Mathcamp offers mathematically gifted high schoolers classes in advanced math, exposing them to undergraduate- and even graduate-level topics in pure and applied math. In addition to classes, students work on projects, either individually or in groups, culminating in a project presentation at the end of the session. Mathcamp doesn’t impose requirements or a set curriculum on students and, instead, offers them the freedom to self-direct their time and choose what they want to learn. Mathcamp is competitive, accepting 15 percent of students in recent years.

Location: A different college campus each year

2025 Location: Lewis & Clark in Portland, OR

Cost: $6,600 (financial aid is available, and the program is free for families earning under $100,000 per year)

Length: 5 weeks

Science and research summer programs for high school students

Research Science Institute (RSI)

Description: RSI pairs scientific coursework with a research internship to allow students to “experience the entire research cycle from start to finish.” Students work on individual research projects under the mentorship of veteran scientists and present their findings at the program’s conclusion. RSI accepts 80 students each year.

Location: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA

Cost: Free

Length: 6 weeks

The Summer Science Program (SSP)

Description: SSP is an immersive, research-based program that has been running since 1959 and is governed and operated by its own alumni. Students choose one of four programs—Astrophysics, Biochemistry, Genomics or Synthetic Chemistry—and participate in classroom work, lab sessions, guest lectures, and field trips. Open to current sophomores and juniors, admission to SSP is competitive, with an acceptance rate around 10 percent.

Location: Various college campuses across the United States (2025 locations include New Mexico Tech, University of Colorado–Boulder, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Purdue University, and Indiana University)

Cost: $9,800 (financial aid is available, and the program is free for most families earning under $75,000 per year)

Length: 39 days

Stanford Institutes of Medicine Summer Research Program (SIMR)

Description: At SIMR, students perform medical research with Stanford faculty and researchers. Students choose from one of eight research areas and are subsequently assigned to a corresponding lab where they receive one-on-one mentorship. Open to current juniors and seniors, SIMR heavily favors applicants from the Bay Area, as it does not provide housing. Around 50 students are accepted each year.

Location: Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA

Cost: Free with a stipend (stipend amount varies but is $500 minimum)

Length: 8 weeks

Minority Introduction to Engineering and Science (MITES)

Description: MITES is for academically talented rising seniors—often from underrepresented or underserved backgrounds—who are interested in careers and advanced degrees in science and engineering. Students take five courses as well as participate in admissions counseling sessions, lab tours, and social events.

Location: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA

Cost: Free

Length: 6 weeks

Simons Summer Research Program

Description: Simons is a hands-on research program in which students participate in an existing research group or lab and take on a project under the supervision of a faculty mentor. Participants also attend weekly faculty research talks and participate in special workshops, tours, and events. Students must be current juniors and must be nominated by their high school in order to apply. Simons is highly selective, admitting around 5 percent of applicants.

Location: Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY

Cost: Free

Estimated residential costs for 2024: $2781.50 (includes $600 meal plan; and $61.50 Student Health Services Fee)

Length: 7 weeks

Summer Academy for Math and Science (SAMS)

Description: SAMS is for current sophomores and juniors from underrepresented backgrounds who wish to “develop mastery of critical concepts in higher-level collegiate math and science” while earning college credit. SAMS includes classroom instruction, hands-on projects, and professional and academic development workshops.

Location: Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA

Cost: Free

Length: 6 weeks

Research in Science and Engineering Program (RISE)

Description: RISE is a program for rising seniors that consists of two tracks: Practicum and Internship. Internship students conduct individual research projects in a university lab under the guidance of a mentor, while practicum students collaborate on group neurobiology research in a structured environment overseen by an instructor. RISE is selective, accepting around 9 percent of applicants.

Location: Boston University, Boston, MA

Cost: $9,461 residential; $6,185 commuter (financial aid available) + $60 application fee

Length: 6 weeks

Description: The Jackson Laboratory Student Summer Program is a genetics and genomics research program for undergraduates and high schoolers who are 18 and have completed grade 12 at the time of participation (i.e., current seniors can apply). Students spend the summer immersed in an independent research project under the supervision of a mentor, presenting their findings at the end of the program. Admission is highly competitive—just 40 students, or around 3 percent, are chosen each year.

Location: The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME

Cost: Free with a stipend ($6,500)

Length: 10 weeks

National Institutes of Health Summer Internship Program (SIP)

* Note: HS-SIP has been discontinued and merged with SIP.

Description: SIP gives students the chance to perform full-time research in the biomedical, behavioral, and social sciences. Students are given the opportunity to explore basic, translational, and clinical research at NIH facilities, working alongside scientists who are global leaders in the field. Eligible applicants must be seniors at the time of application and at least 18 years old by the start of the program. Unfortunately, the NIH does not provide housing.

Location: NIH campuses in Bethesda, Baltimore, and Frederick, MD. Limited numbers of positions are also available in Hamilton, MT; Framingham, MA; Phoenix, AZ; and Detroit, MI.

Cost: Free with a stipend ($2,530 - $2,840 per month)

Length: 8 weeks

Business, economics, and tech summer programs for high school students

Bank of America Student Leaders Program

Description: Student Leaders assigns paid internships at local nonprofits to juniors and seniors interested in honing their community and business leadership skills. Participants also attend a one-week summit in Washington, D.C, where they meet with members of Congress and participate in projects and workshops focused on societal engagement. Around 225 students are chosen each year to participate.

Location: A nonprofit organization in your local area plus a 1-week summit in Washington, D.C.

Cost: Free with a paid internship

Length: 8 weeks

Leadership in the Business World (LBW)

Description: LBW offers current sophomores and juniors an introduction to business through classes with Wharton professors and visiting business leaders, as well as visits to company offices and team-building exercises. A highlight of the program is the opportunity for participants to create and present their own business plan to a group of venture capitalists and business professionals. Approximately 120 students attend LBW each summer.

Location: The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Cost: $11,399 (financial aid available)

Length: 4 weeks

Description: Economics for Leaders “teaches leaders how to integrate economics into the process of decision-making in a hands-on, experiential environment.” Students typically spend mornings attending economics lectures and afternoons and evenings in leadership workshops and exercises. Open to current sophomores and juniors, 25–40 students are accepted at each site. College credit is available.

Location: Various college campuses across the United States

Cost: $2,300 (limited financial aid available) $800 (EFL Virtual) + $35 application fee

Length: 1 week

Description: The Young Women’s Institute offers young women an introduction to the world of business through workshops taught by Kelley School of Business faculty, the opportunity to design their own business case project, and presentations on business skills. The Institute is open to rising juniors and seniors. Virtual programs are open to rising sophomores, juniors, and seniors.

Location: Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Cost: Free

Length: Varies by program.

Description: LaunchX is an entrepreneurship program that supports students through the process of launching an actual startup. Students attend workshops, lectures, simulations, and panel discussions that help them locate a need in the market and create their own business to fill it. LaunchX is open to all current high school students and admits around 18 percent of applicants.

Location: Various college campuses across the United States or online

Cost:

Online BootCamp Summer Program $1,995

Online Innovation Summer Program $4,995

Online Entrepreneurship Summer Program $6,995

USA In-Person Entrepreneurship 1: $9,995 (financial aid available)

Bay Area Entrepreneurship Summer Program $9,995 (financial aid available)

Additional $200 international fee for both on-site programs if you’re not from USA

Application fee (based on date you apply by):

November 15, 2024: $45

January 15, 2025: $60

March 5, 2025: $75

Length: 4 weeks

Girls Who Code Summer Immersion Programs

Description: Girls Who Code is a program for current sophomores and juniors who identify as female or non-binary and are inexperienced in computer science. Participants are introduced to many different areas of computer science, complete a final project in which they build their own product, and participate in workshops and lectures. They also gain exposure to the tech industry by connecting with female tech professionals.

Location: Tech companies across the United States

Cost: Free with stipends available for transportation and living expenses

Length:

Summer Immersion Program: 2 weeks (virtual)

Self-paced program: 6 weeks

Journalism summer programs for high school students

Princeton Summer Journalism Program (PSJP)

Description: PSJP is a program for talented current juniors from low-income households. During PSJP, students attend workshops and lectures, tour leading news outlets, cover real events, and conduct investigations in preparation for the creation of their own newspaper, which is published on the last day of the program. Participants also get the benefit of college counseling with PSJP staff after they return home. PSJPS is competitive, accepting 40 students each year.

Location: Princeton University, Princeton, NJ

Cost: Free

Length: 10 days

Program Dates: Exact dates not listed but online workshops begin in mid-July and the program finishes with a 10-day residential experience on Princeton’s campus in early August.

Description: SJI is a broadcast and digital journalism focused program that gives students hands-on experience in a variety of areas of journalism, from reporting to production to camera work. Students also get to tour local newsrooms as well as work in state-of-the-art on-campus broadcast facilities.

Location: Arizona State University, Tempe Phoenix, AZ

Cost:

Sports Media: $899 (need-based scholarships are available)

Media: $799 (need-based scholarships are available)

Length: 2 weeks

Description: JCamp provides students with workshops, field trips, and hands-on instruction from professional journalists in a variety of areas, including writing, photography, broadcasting, and more. Originally founded in response to a shortage of diversity in the media, JCamp emphasizes multicultural perspectives. Open to all current freshman, sophomores, and juniors, JCamp admits around 40 students each year.

Location: Georgia Public Broadcasting, Atlanta, GA

Cost: Free

Length: 6 days

Creative writing summer programs for high school students

(Note: Some programs in the following category also offer creative writing.)

Description: At the Iowa Young Writers’ Studio, students take a workshop and seminar in a single course of study—poetry, fiction, or a creative writing survey. In addition to sharing their writing and receiving critiques from teachers and peers, they also attend readings and other literary events. The Iowa Young Writers’ Studio is open to all students who have completed their sophomore year.

Location: University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA

Cost: $2,500 (in-person) + $10 application fee (need-based financial aid available)

Length: 2 weeks

Kenyon Review Young Writers Workshop

Description: Young Writers is a creative writing program for 16–18 year olds in which students spend five hours per day in multi-genre workshops. Participants also conference individually with their instructors, take genre-focused mini-workshops, and attend readings from visiting writers.

Location: Kenyon College, Gambier, OH

Cost: $2,575 (residential) $995 (online) (financial aid available)

Length: 2 weeks

Arts summer programs for high school students

Description: Interlochen offers students in grades 3–12 courses in a variety of arts disciplines: creative writing, dance, film and new media, interdisciplinary arts, music, theatre, and visual arts (note that students must apply and be accepted for a specific discipline). Though the range of ages at Interlochen is wide, high school students form their own divisions of 10–16 students who live and dine together.

Location: Interlochen Center for the Arts, Interlochen, MI

Cost: Varies by length, e.g. $1,950 for one week or $10,180 for six weeks (financial aid available for all sessions except one week)

Length: 1–6 weeks

Program Dates: Varies by session length

Idyllwild Arts Summer Teen Programs

Description: Students ages 13–18 can apply to enroll in immersive workshops in creative writing, dance, fashion design, filmmaking, music, theater, or visual arts. The format of the program varies according to the discipline, but most culminate in a performance, reading, or exhibition. Note that certain disciplines are open to beginners while others require prior experience and portfolios or auditions to be accepted.

Location: Idyllwild Arts, Idyllwild, CA

Cost: Varies by length and program, e.g. $1,090 per week or $5,025 for four weeks (financial aid available)

Length: 1–4 weeks

Foreign language summer programs for high school students

National Security Language Initiative for Youth (NSLI-Y)

Description: NSLI-Y is a study abroad program sponsored by the United States Department of State that offers intensive language instruction in eight less frequently learned languages: Arabic, Chinese, Hindi, Indonesian, Korean, Persian, Russian, and Turkish. NSLI-Y “aims to guide students toward using language in their university and/or professional careers and to dedicate themselves to continued language learning far beyond their time on the program.” Highly structured and immersive, participants live with host families and participate in cultural activities.

Location: Various foreign countries in which students can study one of eight less commonly taught languages

Cost: Free (sponsored by the United States Department of State)

Length: 6–7 weeks

Wilderness summer programs for high school students

Student Conservation Association National Crews

Description: National Crews gives 15–19 year olds the opportunity to work on parks restoration projects and trail maintenance in crews of 6–8 students. Students live in tents, cook their own food, learn outdoor skills, and learn about ecology and the environment. Sites include national, regional, state, and local parks. National Crews is moderately competitive, accepting fewer than half of all candidates.

Location: National parks and public lands across the United States

Cost: Free (participants are responsible for their own transportation and gear)

Length: 2–5 weeks

Volunteer and travel abroad summer programs for high school students

Description: Putney Student Travel has been operating for nearly 70 years and has a reputation for carefully planned programs that emphasize “community empowerment, cultural diversity, and environmental sustainability.” Putney Student Travel runs service-oriented trips for high school students to eleven different countries, as well as trips with other focuses, such as language immersion, mountain climbing, and zoology.

Location: 32 countries around the world

Cost: $5,090–$7,990 - for service-oriented programs (financial aid available) + $200 Application fee

Length: 13–29 days - for service-oriented programs

Description: Rustic Pathways offers trips for 12–22 year olds that are designed with sustainability and local community development in mind. Offering a mix of service, adventure, and cultural immersion trips, Rustic Pathways programs “are intentionally designed to challenge students to think critically and experience personal growth” and are designed collaboratively with local partners according to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Location: 20 countries around the world

Cost: $2,595–$7,995 (for student programs), excluding airfare

Length: 12–22 days

The Experiment in International Living

Description: Founded in 1932, The Experiment focuses on learning from foreign countries rather than teaching, and emphasizes cultural sensitivity, sustainability, and social responsibility in its programs. Offering service and non-service trips alike, program focuses vary from public health to the environment to language and cultural immersion.

Location: 14 countries around the world

Cost: Varies by location e.g. $6,350–$8,413 + airfare

Length: 3–4 weeks

Global Vision International (GVI)

Description: GVI runs programs focused on sustainable development and experiential education which are guided by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals as well as the goals of local partners. GVI offers a selection of volunteer trips specifically for teenagers under 18, the majority of which focus on environmental conservation and community development.

Location: 10 countries around the world

Cost: Varies by program but typically ~$3,645

Length: 2 weeks

Program Dates: Varies by program

Application Opens: Currently open

Application Deadline: Varies by program

Alternatives to summer programs for high school students

There are many good alternatives to attending summer programs that your child ought to consider.

If your child is interested in having an academic experience over the summer, but pre-college programs are out of reach academically or financially, they might consider enrolling in a course at a local community college. Community college courses are much cheaper than pre-college programs, and your child will still exhibit academic passion, plus some extra initiative. An internship or research project with a local college professor would demonstrate similar qualities.

Community service is another great way to spend the summer close to home, so long as your child’s service isn’t perfunctory and reflects their genuine commitment and interest.

Your child may also want to consider the old-fashioned summer job. In addition to the obvious benefit of earning money, jobs also teach students responsibility, work ethic, humility, and teamwork. Though your child won’t be building robots or analyzing 19th-century literature, the personal qualities your child will likely gain are impressive to admissions committees and are not necessarily easy to learn from highly structured summer programs.

Attending a pre-college summer program can be a fantastic experience for your high schooler, so long as the program is challenging, within your family’s financial means, and not counted on as a backdoor into a prestigious college. There are also many other good options that your child can pursue to stay engaged and challenged over the summer. If your child is interested in attending a summer program, be sure to research the program’s quality and choose a subject that’s in line with their interests and specializations.

How to Stand Out on the Common App Activities Section

Learn how to share your accomplishments in a way that shines, plus a Common App Activities section example

Common App Activities section overview

In addition to the dreaded 650-word Common App Essay and the numerous college-specific supplemental essays your child will have to write, they’ll also need to complete the Common App Activities section when applying to college.

Whereas the Common App Essay will show college admissions committees who your child is, the Common App Activities section will allow colleges to understand what your child has done and is doing outside of the classroom, offering one of the best opportunities to stand out among other applicants.

Without college essays and extracurricular activities lists, colleges would be limited to grades, class rank, and ACT and SAT scores to make their admissions decisions. Given that so many students with strong numbers apply to college each year, it’s important for your child to use the Activities section to develop an application theme—that is, to highlight their “it factor” and specialties.

Before we get into writing tips and sample extracurricular descriptions, let’s go over a few Activities section basics:

What qualifies as an activity?

According to Common App, “activities may include arts, athletics, clubs, employment, personal commitments, and other pursuits.” In other words, pretty much anything pursued outside the classroom qualifies as an activity.

Since nearly anything counts as an activity, can my child include activities done on an informal basis?

Yes. Your child can include activities that were organized formally as well as those activities that may have only involved your child. Examples of the former might be sports teams and school clubs whereas examples of the latter include activities and hobbies your child may also participate in independently, such as reading or scrapbooking. Additionally, your child may perform community service as part of a team or alone. Either way, it could count as an impactful activity for the Common App.

How many activities can be listed?

Your child may list up to 10 activities.

What are the word or character limits for each activity?

Common App sets the following limits for each activity:

Position/Leadership description: 50 characters

Organization name: 100 characters

Activity description, including what your child accomplished and any recognition they received: 150 characters

As you can see, there is very limited space offered for each activity, so we’ll be discussing how to maximize the impact of each entry below.

What other information does Common App collect for each activity?

Common App requests the following information for each activity:

Activity type (e.g., art, athletics, community service, debate/speech, foreign language, research, social justice, work)

Participation grade levels (9, 10, 11, 12, post-graduate)

Timing of participation (during school year, during school break, all year)

Hours spent per week

Weeks spent per year

Whether or not your child intends to participate in a similar activity in college (yes/no)

(Note: It is acceptable for your child to indicate their intention to participate in certain similar activities in college, but not others.)

Writing strategies

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s discuss some proven approaches to completing a strong Activities section:

1. Include role and organization name in their respective boxes.

The first four fields for each activity on Common App look like this:

After selecting an activity type from the drop-down menu, your child should input both their position and the organization name in the corresponding boxes. That way, your child can use the full 150-character limit for the activity description box.

For example, your child should write “President” followed by “Student Council.”

2. Do not repeat words from the position description box in the activity description box.

Continuing with the student council president example: Instead of writing, “As president of the student body, I was responsible for…”, your child should write, “Implemented school initiatives such as free textbooks for low-income families, liaised with administration, and curated meeting agendas.”

3. Focus on quantifiable and significant impact.

Many applicants undersell their achievements because they don’t get specific enough about their contributions. For example, rather than writing something like, “Organized food can drive for local families,” your child should write, “Collected over 10,000 cans and provided Thanksgiving meals for 500 families in greater Cleveland.” With details like that, your child’s impact will be unquestionable to admissions committees.

Numbers also have a way of jumping out to a reader and demanding attention, and they can help break up long strings of text that a reader might have otherwise been inclined to skim over.

4. List tasks and avoid complete sentences to make room for more detail.

Colleges understand that your child does not have enough space to provide in-depth descriptions of each activity. Therefore, rather than write, for example, “At the hospital, I transported patients with physical disabilities on wheelchairs…”, your child should write, “Transported patients on wheelchairs, provided meals and blankets, assembled gift baskets, and attended grand rounds.”

Think of these descriptions more as bullet points on a resumé. It’s a good idea to begin each description with a strong descriptive verb — words like implemented, led, founded, tutored, established, managed, launched, etc. catch the reader’s attention and help them envision your child actively engaging in the activity.

Stick to direct pieces of information and cut out any “fluff” or filler information. While using proper grammar is still important, it’s also acceptable to eliminate things that would typically pad your child’s writing, such as prepositions, articles, and pronouns. You may be surprised at just how many characters your child can save by eliminating them!

5. Describe current activities using present tense.

For instance, rather than, “I tutored seventh graders in science,” your child should write, “Tutor 7th graders to help them master challenging science concepts.”

Advanced strategies

What is the best order to list activities on the Common App?

With so many possible ways your child can list activities on the Common App, they may wonder if the order even matters. In a word: yes!

Keep in mind that the Common App specifically instructs applicants to list their activities in order of their importance (to the applicant.) It would also be wise for your child to consider placing at few of their most objectively impressive activities and the activities most closely related to their intended college major close to the top of the list. Moreover, capturing admissions committees’ positive attention early on will compel them to review the rest of your child’s activities list more favorably.

Your child should list activities that best illustrate who they are as a person and how they prefer to spend their time. Activities that don’t tell anything about their interests or possible future career endeavors don’t need to be included. Remember, the experiences listed in this section should be noteworthy and indicative of who your child is, so choose wisely and order them accordingly.

1. Make activities sound as impressive as possible.

Dr. Cal Newport first popularized the concept of the failed simulation effect, defined as follows: “Accomplishments that are hard to explain can be much more impressive than accomplishments that are simply hard to do.” Therefore, within each activity’s description, your child should describe accomplishments that are hardest to explain. For example, if your child blogs about mental health and had an opportunity to meet with a local city councilperson to develop a mental health awareness initiative in your county, they should mention that. It’s important to note, however, that your child should never fabricate or exaggerate achievements and extracurricular activities for the sake of impressiveness.

Common App Activities section example

Below is an example of how a single student might format, describe, and order their activities.

Intern

Google Virtual Reality (VR)

Coded VR environments for various software prototypes, some of which were featured at the 2017 Consumer Electronics Show.

Founder and President

Code for Community

Organize coding camps for middle and high schoolers from inner-city Chicago whose schools do not offer computer science classes.

President

Coding Club

Major projects include developing software for school to track student grades, assignments, and parent communications.

Assistant Instructor

Tae Kwon Do

Train 5- to 6-year-old martial arts students to develop proper technique and instill confidence.

Tae Kwon Do

Achieved black belt at age 16 and currently training for state tournament.

Writing Peer Counselor

The Hamilton School

Supported high school students with all forms of writing, including in-class assignments, AP exam essays, and school newspaper articles.

Math Tutor

The Hamilton School

Support struggling middle and high school students with Algebra 1 and 2, Geometry, Precalculus, and Calculus.

President

Cru Club

Host monthly speaking events with athletes, principals, etc. for 80 students from all over Chicago to help them discover aspects of their purpose.

Customer Service Representative

Elegant Cleaners

Greeted customers, processed orders and payments, and returned clothing items.

Waitress

Blue Ribbon Diner

Took customer orders, served food and drinks, and processed payments.

In the above example, the student does a fantastic job ordering their activities in a hierarchical manner so that the most impressive activities are at the top. Remember that colleges receive tons of applications, so you need to stand out early.

In addition, their descriptions read like a resumé, avoiding complete sentences and being stripped of unnecessary phrases. This student also does a good job showcasing a commitment to their community through their activities.

Also, notice that similar activities are grouped together. This gives colleges a good idea of an applicant’s interests and what they might contribute to the campus community.

What is a Public Ivy?

What is a Public Ivy?

When parents think of colleges with reputations for excellence, Ivy League schools usually top the list. In addition to providing quality educations, the eight Ivy League schools-Harvard, Yale, Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, Brown, Dartmouth, Cornell, and Columbia-are well known as highly selective, private institutions.

But many parents are unaware of a lesser-known alternative that offers the prestige and academic rigor of an Ivy League school: the Public Ivy.

The term the term “public ivy” was coined in 1985 by Richard Moll to recognize schools with, in addition to a reputation for academic excellence, “the look and feel” of an ivy league school.

When comparing the experience of attending a Public Ivy to the experience of attending an Ivy League school, there are a few key differences to keep in mind.

A Public Ivy tends to be larger than Ivy League schools

One significant difference is typically size, both in terms of a school's overall undergraduate population and its student-faculty ratio. For the most part, Public Ivies tend to have undergraduate populations in the tens of thousands while most Ivy League schools enroll under 7,000 undergraduates.

For example, UCLA currently reports just over 33,000 undergraduates and a student-faculty ratio of 19:1, whereas Princeton’s undergraduate population is usually around 5,500, giving it a much lower student-faculty ratio of 5:1.

Lower student-faculty ratios are often considered desirable since they mean that a student is more likely to receive individualized attention from their professors. On the other hand, larger undergraduate populations tend to be more diverse and have a wider range of extracurricular and social activities for students to participate in. Classes at a big school may fill up more quickly, but there will typically also be a larger course catalog to choose from.

Your child will ultimately want to consider their own academic and social needs when considering school size, as well as do individualized research on specific schools. At Public Ivies, they’ll find a diverse array of student organizations and clubs. From cultural and ethnic groups to recreational sports teams and volunteer organizations, there are countless opportunities for students to engage with like-minded peers. For example, the University of Michigan has over 1,600 student organizations, while the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill offers more than 600 clubs and groups.

Public Ivies also frequently host cultural and social events ranging from concerts and festivals to lectures by renowned speakers and art exhibitions. For example, UC Berkeley's Cal Performances series features world-class music, dance, and theater performances, while the University of Michigan's Ann Arbor campus is known for its vibrant arts scene and annual festivals like the Ann Arbor Art Fair. Events like these will enrich your child’s cultural awareness and also provide opportunities to network with the broader community.

This isn’t to say that your child won’t find these opportunities at Ivy League schools, but because of their smaller size, they tend to have more tightly knit campus communities. Your child may find more opportunities to showcase their leadership skills and engage in a broader range of activities at a Public Ivy.

Many Public Ivies offer more intimate or advanced programs nestled within them, which provide students with a smaller community as well as special academic and social opportunities. Often known as “honors programs” or “honors colleges,” these programs can range in scope from primarily academic to those that encompass both residential life and coursework.

An example of the latter can be found in the University of Michigan's Residential College, where a select group of students live and take classes, often focused on the humanities and arts, in the same building (freshman class size: 250).

On the other hand, the University of Texas’ Plan II Honors Program offers a liberal arts-style interdisciplinary curriculum and special social opportunities like student dinners and reading groups (freshman class size: 175).

A Public Ivy encompasses a wider range of academic reputations

Though challenging academic programs can be found at any Public Ivy, it's worth keeping in mind that some Public Ivies are recognized as all-around academic powerhouses, comparable to an Ivy League school, while others may be renowned for a particular program or department.

A great example of the former is UC Berkeley, which is considered among the best universities in the country with high-ranking programs across a wide variety of disciplines. In contrast, Georgia Tech is a top school for engineering and UC San Diego is lauded for its biology department.